24 hours in Warszawa, May 1999

It was my first time in Poland for ten years; the last time was in the months following the fall of the Berlin wall, when conversation was full of hopes and doubts; and the year before that, the first visit to the village in the north, when I wanted to stay forever... the beautiful landscape, the children playing in the rye fields and the horse-drawn villagers Sunday-dressed while nine storks circled in a sun-filled sky... but the men were drowning in vodka, the towns were holed and train-men took bribes of caviar and trinkets instead of visas... villages were littered with half-built houses of grey blocks, and the towns built of two-room appartments for families of five, or six...

| Arriving at the airport, SwissAir from Zurich; a plane full of French and German businessmen, three off-duty Polish stewardesses and one or two Polish tourists, greeted by uniformed officials, fewer than ten years ago; the airport is new, the waiting taxicabs newer still. The road from the airport is lined by advertisements and the small hotels found the world over. The smell of cheap exhaust-fumes is less than before; and I see signs for French supermarkets and America Online. |

|

|

Wandering the streets before and after work: everything is

newer, cleaner; even the clothes are less grey. The only other

person I saw wearing black was a uniformed soldier, or policeman,

buttons shining in the sun. The day was hot, sunny; memories of

the village in the north; wondering if all has changed there,

too; if the small shop-in-a-hut has been replaced by a multi-storey

glass monument to Capitalism; if the carts have been painted

with advertisements for Carrefour or Coca-Cola...

|

| The streets are now lined with Fiats, Renaults, Citroens, Volkswagens, Fords, and the odd Mercedes. Dusty from the Polish sand-soil, but shining through. The roads are still bumpy and uneven, but the signs are bright and the traffic moves and drivers obey the traffic signals. I could have been in any French city, except for the traffic stopping to let pedestrians cross the road. |  |

I took a taxi across the river to my business rendez-vous. Not in a new, glass-faced office block, but tucked away in a converted house near the television company, in the heart of appartment-land. Builders working on the renovation of no-longer-grey-faced buildings. Sand and cement-mixers spilling onto the streets. I was early and crossed the road, wandered into the gardens; not a park or public flower-show, but an area of garden allotments in the center of the city. Cinder paths and the birds singing. City gardens like part of a village transported here years ago under the watchful eye of big brother: small wooden summer-houses, neat rows of lettuce, of green beans, of onions: rubarb growing in nocturnal corners, bushes heay-laden with lilac hanging over the scented heavy-headed ruby flowers that filled the village, and the nightingale that sang and sang all night long while his wife warmed the eggs.

It was a stroll back in time; to the village in the north, to the war-abandoned Poles in England, to my ninth-year summer in the wooden army bungalow between houses, when my dad was fitting wooden seats into Auster Aircraft and he flew to Cambridge and it was half-a-world away, he brought us back presents because he was away overnight... and we lived that summer with the Poles who had been given the wooden bungalows as home, when they couldn't return to theirs, and they remade the gardens in their own style, lilac and peony and chickens and rabbits and cabbage and onions and vodka.

| But in Warsaw today, the gardens are a reminder of the past; the occasional battered car a finger pointing at what was, and what would be if there were no dollars, no francs or pounds; and no McDos? |  |

The trams pass every few minutes. No longer servile,

grimy beasts carrying overalled Solidarity to their factories,

they are multi-coloured living advertisements for everything

from painkillers to supermarkets, insurance companies to

portable telephones...

The trams pass every few minutes. No longer servile,

grimy beasts carrying overalled Solidarity to their factories,

they are multi-coloured living advertisements for everything

from painkillers to supermarkets, insurance companies to

portable telephones...

Notices in the English visitor's guide warn "not to act like a

tourists", not to leave cars in unguarded places, not to walk

alone, almost to expect violence and mafia-work on the streets.

I couldn't see into the souls of the people, and couldn't

tell if a new elite had replaced the old guard. I walked the

sunny, dusty streets unnerved only by male stares. But the farms

outside the city were still cut into medieval stripes.

| The old city was rebuilt after the war; a monument to the indestructibility of the Polish soul? Today the parties of schoolchildren giggle and look as always; and now they are dressed like children everywhere. Youths in baggy shorts, flash T-shirts and cropped hair. Techno posters and CDs. Could be anywhere... |  |

|

The old market square, its buildings reminiscent of Belgium, Holland, its colours all its own... the early-morning square waiting for visitors to wake it, to shake it into life... one streetside stall selling crochet and carvings; books books books throughout the city, for sale on every corner, and everyone buying, reading, reading, books and papers, papers and books. |

| A "bocian", the stork, keeps watch on his countrymen from the corner of an old-town square; old men dream in the sun, comfy in their carriages, waiting for a tourist or two to walk their heavy horses through the cobbled, painted streets. |  |

|

|

| I walk to the site of the Warsaw Ghetto. I walk because I can't figure out how to pay for a tram ticket, and because it's sunny, and because in walking in a strange town you get to know it through the stones against your feet, the melting tarmac, the litter and the uneven paving that trips you as it trips the inhabitants who walk there day-by-day, carrying their shopping in plastic bags torn at the edges and walking their dogs and going to the kiosk for Marlboro's, made in Poland under licence... |

|

The ghetto has long-gone, built over and replaced by a jungle

of appartment buildings, now looking hopeful in the sun; again,

it could have been France, it could have been Germany,

these streets of five-floor flats with washing hanging on the

balconies and old women sitting in the little green parks and

men going for their newspapers and a gossip.

Mila 18 is a bank, or an office block, maybe appartments or a greenish square; I couldn't figure out which; the ghosts are remembered by a few stones set in a small square of stunted grass and bushes. New buildings look down on the woman at the memorial. She circles it three times, as if in ritual prayer... but no, she is only exercising her Doberman in the early morning sun. |

|

| A big open space, the site of the ghetto where so many Polish Jews lived and died, where they rose up fighting for their freedom, where they lost their lives, and lost their children, parents, brothers and sisters, now it is this big, open, liberated park with mature horse-chestnut trees spreading shade and lighting the night with their candle-flowers. A grey monumental carving watches over it all, horror in the eyes, do not forget, it could happen, it did happen, don't let it happen again. |

|

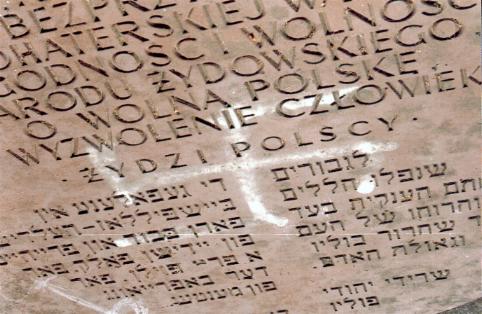

And still... a memorial stone, engraved in Polish and Hebrew, sitting in the sun for all to see: it is embellished with a crude swastika, and no-one has bothered to remove it.

And the streets are full of McDonalds and Fiat and internet and soft-pornography and French supermarkets, and the four-star hotels are housing French and German businessmen, and the staff all speak English, and half the city are talking on portable phones and grey and black are out-of-place... I had to search for a traditional Polish breakfast, not croissants or fast-food but tomatoes that taste like they only do in Poland, and ham and white cheese and fresh fresh bread, and a glass of coffee with the gritty grounds in the bottom... and half of me wanted to hire a battered car and drive to the north, to see if the village had changed at all, to see if the night dogs were still tied in the dusty street and if the bocians still nested on the pole behind the schoolhouse, to see if the sun still rose over Russia and set over the west, to see if the men still sat with their bottles of piwo outside with the dogs and horses and tractors, while their wives listened-in-love with the priest who told them that alcohol was not a good thing... to see the eels wriggling fresh from the lake, escaping from the scrumpled newspaper across the floor of the barn... to watch the chickens scratching in the yard ready for tomorrow's soup, and the too-much food and over-hospitality, the men sneaking off into the sunset rye to spice their tea with a little more vodka...

Half of me wanted to drive north and find the little village, down the narrow road from the small town with its Prussian buildings, past the railway station that looked like an escapee from a worldwar two movie, complete with steam-spouting engines...

But the other half of me won. I was afraid to see the changes... and I wanted to keep the good memories, and throw away the bad. Too many dreams, and too many black nights. And I had a plane ticket for midday, and my daughters waiting at home, and work, and life going on in its usual rolling way so I took the easy taxi to the airport, and waited there among the German and French businessmen, and watched the grey-haired guitarist and his band, waiting in the sun, waiting for the wings to fly... he might have been famous, or just someone else's dream.

Poland; you have changed, are changing, as we all do. But you have your own heart, you own art: let it show through the posters, the hamburgers and the hypermarkets. West is not necessarily Best. But you never did know that, did you????

|

|