|

From the moment that I heard that you had gone, I kept talking to you...

talking to you as if your were standing or sitting or walking next to

me, like a small child telling her father about a day at school, a

visit to the zoo or a hairy caterpillar found in the garden. I told

you about the mountains, described the walnut trees and the shuttered

houses; the people on the train and their sleepy, pretty, plain,

cheerful and tired faces; the ticket machines that you have to use

four times before they stamp your ticket in the proper place; the

sun going down over the bare fields that in summer are filled with

the smiling faces of sunflowers; talked to you about your grandchildren,

and how your only grandson wanted to play cricket with you; about our

made-in-France house, with the balcony facing the sun and the backdrop

of rock and waterfall, now that you would no longer be coming to visit

when the spring arrived. All the journey long from new-home to old-home,

by car, train, boat, train, car... back to your home town, my home town,

where now I was only a stranger among familiar faces.

|

Only the night before, the New Man had loudly chastised me and my distant sisters for not demonstrating our love for you loudly enough. But only a few days before, I'd called you and talked a while - and I'd told you what a father you'd been to me... and only a moment before, my heart had sent out its regular, always-always beat of love to you...

And I phoned my youngest sister in Sydney a few afternoon minutes later, in the middle of her night. And I could not hold her in her tears, because she was half-a-world away. She had to find an airticket and a plane: and I found myself sitting on the floor of a high-speed bar on the train and paying off the guard, because it was a public holiday and there were no tickets available for trains, planes or the bus. And I talked to you... dragging the suitcase across and under Paris, I talked to you... smoking across the winter channel in a half-empty ferry, I talked to you... and I hoped you could still hear me.

|

I came to see you one last time. Your old friend, who had washed and

dressed and prepared you for your final day's work, was standing outside

the cold room with warm and naked tears running down his undertaker

face.

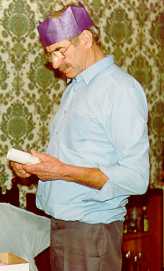

You were marble; beautiful marble, your hands still scarred and chipped from the occasional misplaced chisel or mis-struck nail. Your hair was greyer than it had been at Christmas. We'd said goodbye then with waves and hugs and words and blue-eyed smiles. But this time, it was farewell with a kiss, a handful of summer-scented rose petals and a favourite tape-measure placed in your waiting hands. And then your friend closed the door between us.

|

|

|

Back in my old, unheated, childhood bedroom in your home, I could

still feel your presence. The floorboards you'd replaced after one

of you big feet had gone straight through, the door which you must

have rehung after we'd all left home, because it used to open the

other way and now every time I or one of my sisters tried to open

it in the dark, we automatically fumbled for a non-existent handle,

trying to open it from the wrong side; the round window that you had

always wanted to make and one day did; the hole that you'd drilled in

the door of the airing cupboard, so that you could see the little red

light and know if my mother had left the immersion heater on too long;

the tumbledown shed where the seven elderly chickens used to roost;

the garden path where you once found me happily trying to polish the

concrete with your best expensive smoothing-plane; the old swing that

you'd made for us when we'd all been quite small and where I once sat

and cried all afternoon over my first lost-love; the earth that

wouldn't grow anything well no matter how much compost you dug in;

the now-weathered tiles that I'd helped to carry up-a-ladder-and-up-

to-the-top when you spent several summer weeks putting a new roof

over our heads; the smell of freshly cut wood and the sawdust still

drifting about just outside the back door...

|

Thank you for coming to visit. And for always being there. I love you.

Alison